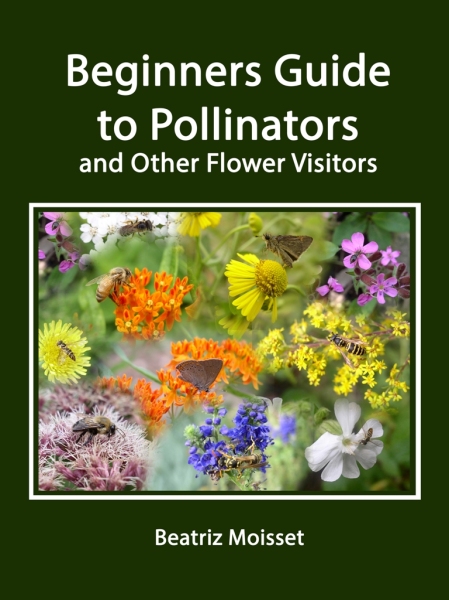

Monarch butterfly on common milkweed

© Beatriz Moisset

The monarch season is coming, and many gardeners throughout the country are getting ready to welcome the arriving butterflies with milkweeds lovingly cultivated in their gardens. They also brace themselves to battle whatever ills may affect the caterpillars. Milkweed bugs and milkweed beetles are seen with hostility. The “dreaded” tachinid flies, and “hated” stink bugs infuriate gardeners even more. Aphids are not welcome. Lady beetles and lacewings generate mixed feelings because they feed on aphids but they are not loath to snack on some monarch eggs or small caterpillars.

Spotted Lady Beetle larva (Coleomegilla maculata)

© Beatriz Moisset

It is important to take a look at entire ecosystems, not just single species as Carole says in “Saving the Monarch Butterfly”

“The Monarch Butterfly is in deep trouble, and many passionate organizations have been created to save this single species. But a focus on protecting habitat instead of concentrating on a single species will provide lasting benefits for all species of wildlife and the native plant communities that support them, a far more worthy effort to many environmentalists and wildlife gardeners.”

So, let us take a quick look at some members of the milkweed community. Despite the formidable defenses these plants have, many species have coevolved with them and can use them as food. They incorporate the milkweed toxins and use them to deter their enemies. In turn, many predators have also coevolved and can eat the milkweed eaters. An entire food chain has developed this way.

Large milkweed bug, Oncopeltus fasciatus on common milkweed

© Beatriz Moisset

Milkweed longhorn beetles on common milkweed

© Beatriz Moisset

Most monarch lovers are familiar with the brightly colored milkweed bugs and milkweed longhorn beetles. Bear in mind that these insects are represented by a fairly large number of species. That is, there are more than just one milkweed bug and one milkweed beetle. A few other beetles also feed on milkweeds, and several moths also do so, among them the tussock moth and the delicate cycnia.

Tussock moth caterpillar

© Beatriz Moisset

Sooner or later, those who raise monarch caterpillars are bound to meet two insects which will make them unhappy; one is a predator, the spined soldier bug, the other a parasite, the tachinid fly, Lespesia.

The spined soldier bug, Podisus maculiventris, is a good hunter of caterpillars and beetle grubs. It has a sharp beak with which it impales its victims. It injects some saliva which turns the inside of the prey into a smoothie and so it proceeds to drink this nutritious cocktail. The sight of a shriveled monarch caterpillar hanging from the beak of a stink bug causes great distress to the gardener.

Predatory stink bug, Podisus maculiventris on goldenrod.

© Beatriz Moisset

Podisus maculiventris juvenile (nymph) feeding on dogbane caterpillar

© Beatriz Moisset

The tachinid fly mentioned above goes by the name of Lespesia. It lays its eggs on caterpillars of a large number of species. The tiny fly larva digs inside and proceeds to eat its victim until it reaches full size. Then it comes out of the dying caterpillar and dribbles a sticky trail until it drops to the ground. Not a pretty sight.

Lespesia puparium and parasitized tent caterpillar’s cocoon

© Stephen Luk

Although these two insects on occasion kill some monarchs, we should not hate them. Actually, their diet is so diverse that it includes a number of pests. They are both used as pest controls for this reason and even sold for this purpose. Podisus is known to eat Mexican bean beetles, European corn borers, diamondback moths, corn earworms, beet armyworms, fall armyworms, cabbage loopers, imported cabbage worms, Colorado potato beetles, and velvetbean caterpillars. The tachinid fly is reported to feed on tent caterpillars, armyworms, cutworms and corn earworms.

Nature is far more complicated than it appears at first sight. It may seem paradoxical, but the spined soldier beetle and the Lespesia fly are indirectly the friends of monarchs, because they help cut down on pesticides. Moreover, we must remember that they have coexisted with monarchs for eons without driving them to extinction. The same can be said about the milkweed herbivores –beetles, bugs and moths. They haven’t driven milkweeds to extinction and they are not likely to do so. We are the ones that pose a threat to milkweeds and to monarch butterflies with our pesticides, habitat destruction and introduction of invasive species.

Let saving the pretty butterfly be the portal to saving the entire community, all the creatures that creep and crawl, the ones that jump or fly and even the ones that kill or get killed. Let us embrace the web of life in its totality, with all its beauty and ugliness.

Delicate cycnia

© Beatriz Moisset

Additional readings

You may find this Flickr album interesting: Milkweed Visitors

More members of the milkweed community

The monarch butterfly as part of the food web: Monarchs and their Enemies

This article first appeared in Native Plants and Wildlife Gardens